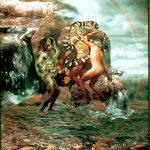

Anna Maria Chupa: Altar

Artist(s):

Title:

- Altar

Exhibition:

- SIGGRAPH 1996: The Bridge

-

More artworks from SIGGRAPH 1996:

Creation Year:

- 1996

Category:

Artist Statement:

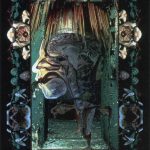

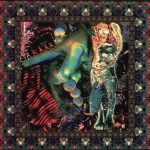

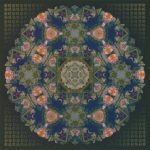

An altar is a meeting place, a point of contact and intersection between human beings and the divine. Damballah, Legba, Guede, and Erzulie are some of the major loa (spirits, mysteries) in the African-Haitian religion Vodun, popularly known as Voodoo or Hoodoo in New Orleans. Damballah’s symbols are the rainbow and the bridge; thus both the SIGGRAPH 96 location in New Orleans and the Art Show theme provide a focus for a Vodun altar installation. The main altar includes a central group of backlighted iris prints, with silk side panels. The space is defined by draped fabric forming a small proscenium stage. A secondary altar exists as a Web site with links to other sites containing related background information and imagery.

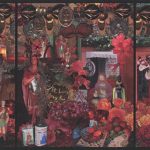

A Vodun altar is created primarily by one designer but the final product is a collaborative effort. Once in place, the altar is never static. The work is thus both participatory and additive. SIGGRAPH 96 attendees can add elements to the altar in two ways: by photographing objects with a digital camera and adding them to the Web site, and/or by physically adding an object to the main altar. In either case, participants add personal commentary, and the altar grows from a personal devotion to a public offering.

Scholars in the field are invited to contribute commentary or images to the Web site. Votive objects purchased ahead of time from local vendors will be available for the viewer to add, or viewers may choose to view the altar and then return with an object. Digitized contributions will be added to the Web site with commentary from each donor. To invite broader participation beyond SIGGRAPH 96 attendees, contacts with community cultural outreach centers will be made in advance, and the Web site will identify related Vodun sites in New Orleans (e.g., Marie Laveau’s tomb) for visitors to the city.

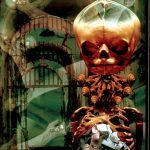

The loa occupy an intermediary position between human life and a supreme being. Translated, the word loa, or lawo, means mystery or spirit. Practitioners are initiated under the protection and guidance of one or more loa with whom they have some fundamental affinity. An altar is constructed for use in the context of an initiation ceremony and for subsequent observances of the faith. Although Vodun and other African-derived religions in the orisa-loa tradition constitute a world faith, they are often misunderstood and misrepresented as exotic cults with voodoo dolls and zombies. As intermediaries, each loa is a bridge between divine agency and human life. Legba is the guardian of the gates, pathways, and communicative exchange. Guede is the loa of the cemeteries and occupies an intermediary position between life and death. Erzulie combines many of the qualities of the archetypal female that are separated in other Western traditions. She is Virgin, Prostitute and Mother. As Erzulie Ge-Rouge, she is the fury of the woman scorned; as Erzulie Freda, she is the virgin of miracles. Damballah is the loa associated with cosmic order and with the cycles of birth, life, death, and regeneration.

Although Vodun, Santeria, and Candomble are distinct diasporic religions, still evolving in Haiti, Cuba; and Brazil, respectively, they share some common African antecedents. I have drawn on common qualities in several altar traditions while attempting not to dilute or demean any of the specific and unique qualities of each.

Some of the imagery, color coding, and symbolism incorporated in this installation will be readily recognizable by Santerian and/or Vodun practitioners. Santerian altars or tronos utilize shapes suggested in the way fabric is draped to honor specific orisa. Fabric bunched in ripples on a ceiling evokes Osun’s waves. Sequined borders might refer to the froth of sea foam for Yemaya. Peaks of white fabric refer to Obatala’s more aloof position on a mountaintop (Brown, 1993). Haitian altars incorporate chromolithographs of Catholic saints. A lithograph of St. Patrick is understood to represent Damballah. African orisa/loa traditions survived to a greater extent in Catholic settings, where it was possible to identify the loa with Catholic saints in order to avoid religious persecution.

Vodun is nonexclusive (Thompson, 1993). Affinities with the symbols and imagery of other religious faiths (most notably Catholicism) are readily absorbed and reinterpreted. My altar borrows imagery from Buddhism, Catholicism, Vodun, and Santeria. After reading a brief overview of the content and symbols, viewers are invited to add elements representative of their own faiths that are aesthetically and thematically consistent with the installation as a whole.

For the non-practitioner, the Web site decodes some of the Vodun imagery. Links to other sources of information on the Web will further instruct the non-initiate. African religions in the Americas have a considerable following, yet they are still marginalized. The artists who construct these altars as private devotions or for public ceremony are similarly relegated to the periphery. The altar and the accompanying Web site serve to instruct the public about the philosophy and origins of Vodun while making a link with a vital part of New Orleans culture.

References

David Brown, Thrones of the Orichas: AfroCuban Altars in New Jersey, New York and Havana, African Arts.Volume XXVI, No. 4 October, 1993.

Robert Farris Thompson, Face of the Gods: Art and Altars of Africa and the African Americans, New York: The Museum for African Art, 1993, p. 20.

All Works by the Artist(s) in This Archive:

- Anna Maria Chupa

-

At the Gates 2

[SIGGRAPH 1997] -

Brain Cell

[SIGGRAPH 1997] -

Assumption

[SIGGRAPH 1997] -

Aengus

[SIGGRAPH 1997] -

Peacock

[SIGGRAPH 1997] -

Descanso

[SIGGRAPH 1997] -

Altar

[SIGGRAPH 1996] -

Nou La

[SIGGRAPH 2007] -

Fava Milagro

[SIGGRAPH 1999] -

Mary's Helpers

[SIGGRAPH 1999] -

At the Gates I

[SIGGRAPH 1997] -

Ezili Freda

[SIGGRAPH 1997] -

Damballah

[SIGGRAPH 1997] -

Saints

[SIGGRAPH 1997]