“Throwing Real Objects Into Virtual Space” by Thiel and Skelly

Conference:

Experience Type(s):

Title:

- Throwing Real Objects Into Virtual Space

Program Title:

- Demonstrations and Displays

Presenter(s):

Collaborator(s):

- George Gomez

- Pierre Maloka

- Richard Ditton

- Ross Toro

- Scott Morrison

- Denise Wallner

- Stan Fukuoka

- Tony Sherman

- Kyle Johnson

- Leif Marwede

- Neil Falconer

- David Marovske

- Dan Dooley

- Randy Tiller

- John Kubik

- Helmuts Eichenfelds

Project Affiliation:

- Incredible Technologies

Description:

As the electronic environment becomes more multidimensional, and more tangible, computer users expect to be able to pass more dimensions of physical information into the electronic universe. In Match Five, a video game with a natural, gestural interface, players peer down into an atrium-like well and use an ordinary cue ball to stop or advance the faces of five floating, rotating dice. The interface reads the entry position, direction, and speed of the ball and translates it to a ball in computer (apparently 3D) space. The user perceives the illusion that the ball’s motion from the real world into the video screen is uninterrupted.?

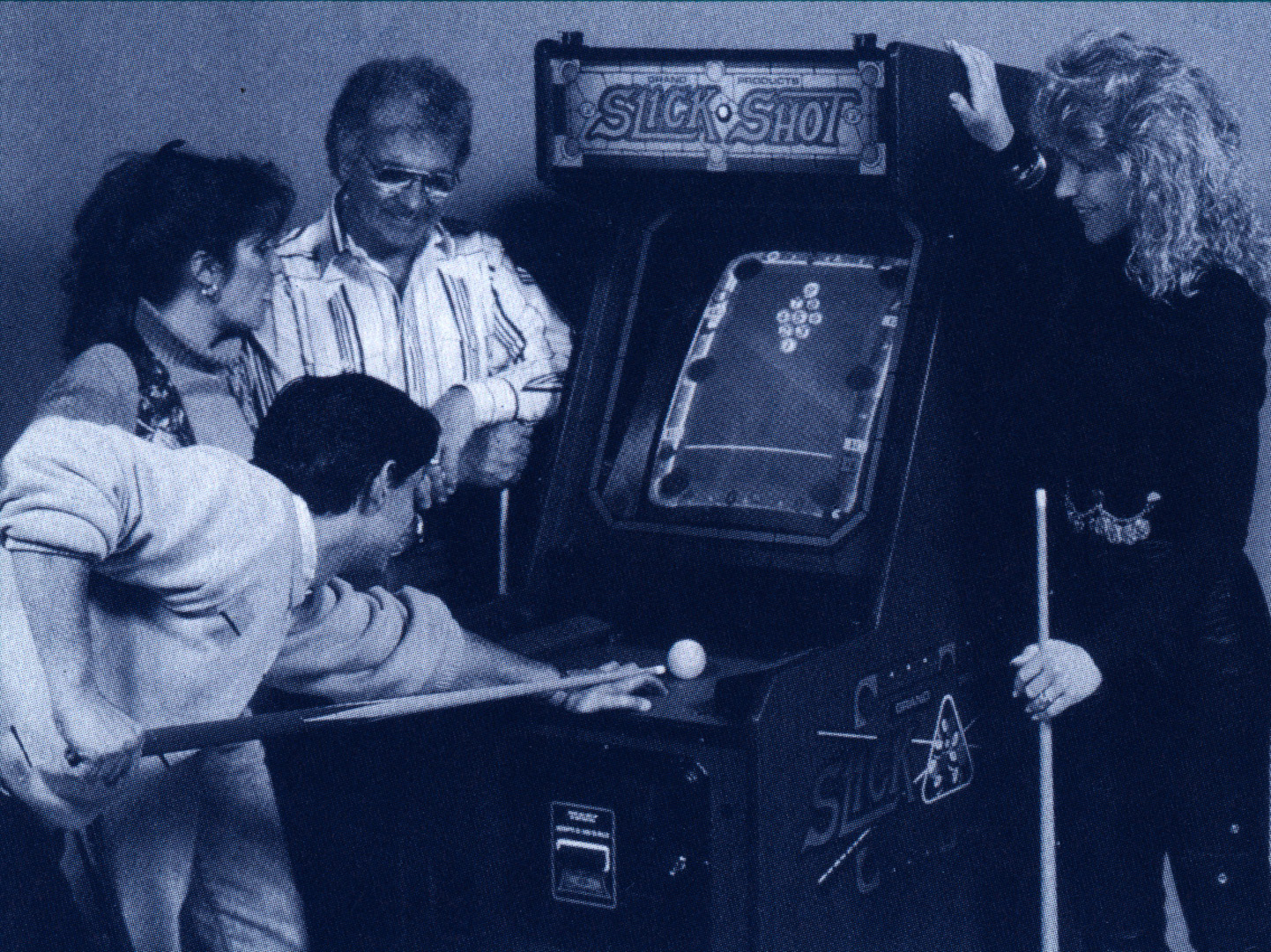

Match Five is the latest in a series of cue-ball-based games developed by Incredible Technologies. The first was Slick Shot, a virtual pool game. Many researchers have encountered problems in attempts to pass parts of human beings – hands, for example – from the real world to the computer world. The problems associated with transporting whole, human pool sharks from one world to the other could prove prohibitive. Fortunately, in a game of pool only the cue ball needs to make the jump from reality to computer model, and less than the entire ball, at that. Since the ball’s relative size and mass are easily assumed, all the computer needs to learn is the ball’s point of origin. direction, and velocity. This is the function of a gestural interface.

When the interface is positioned beneath a monitor displaying the ball’s translation into computer space, the ball can appear to pass smoothly from the real world into the video screen. The hardware needed to play pool with a real cue ball on an unreal pool table is minimal. The interface consists of four carefully arranged infrared transmitter/receiver pairs that are monitored by the computer. Calculations based on the point in time that each pair’s beam is interrupted by the moving ball reveal the ball’s origin, direction, and velocity.

Slick Shot was developed for Grand Products specifically to make use of the flexibility of computer space. A video game takes up far less floor space than a real pool table, so why not create a video pool table for locations that don’t have enough room for a real one?Slick Shot also exploits the mutability of computer space by setting up trick shots with pool balls that seem to move under their own power.

The pool metaphor employed by Slick Shot required the player to move the ball with a pool cue, but rolling the ball seemed to be a more natural and intuitive gesture. Dyno-Bop, another game, was developed to take this into account. It used skee-ball games as a model. Dyno-Bop was quite successful, especially with young children, who had no trouble learning to throw a ball.?

Another natural mapping of the cue ball interface onto an existing activity was Strata Bowling, a bowling game developed by Incredible Technologies for its sister company, Strata. The game originally employed a trackball for player control, but the cue ball device seemed to be a natural for bowling.

These ball-based activities were left behind in the development of Match Five. David Thiel, the game designer, originally believed that simple, geometric modeling of the game space and ball ballistics would yield good results. Oddly, considering the results from the earlier games, this approach left test players feeling that the ball was not hitting the target area at which they were aiming. Though the model was geometrically correct, Thiel adjusted it to conform more closely to player perceptions. He set up a series of trials in which test players were asked to throw the ball through the interface to specific targets on the video screen. No ball was rendered on the screen, however. This simple human factors test gave Thiel enough data to produce ball trajectory translations that match player expectations. The end result is a smooth and highly intuitive interface with virtually no learning curve.

This technology extends far beyond ball games. It can translate the position, direction, and velocity of a cue ball. but it could just as well (if not as easily) translate an object’s mass, temperature, tex-ture, and shape.

The wall dividing the two realities is thin.

Other Information:

Application: Entertainment

Type of System: Player, single-user

Interaction Class: Desktop/vehicle