“Biomimetic eye modeling & deep neuromuscular oculomotor control” by Nakada, Lakshmipathy, Chen, Ling, Zhou, et al. …

Conference:

Type(s):

Title:

- Biomimetic eye modeling & deep neuromuscular oculomotor control

Session/Category Title:

- Looking & Sounding Great

Presenter(s)/Author(s):

Moderator(s):

Abstract:

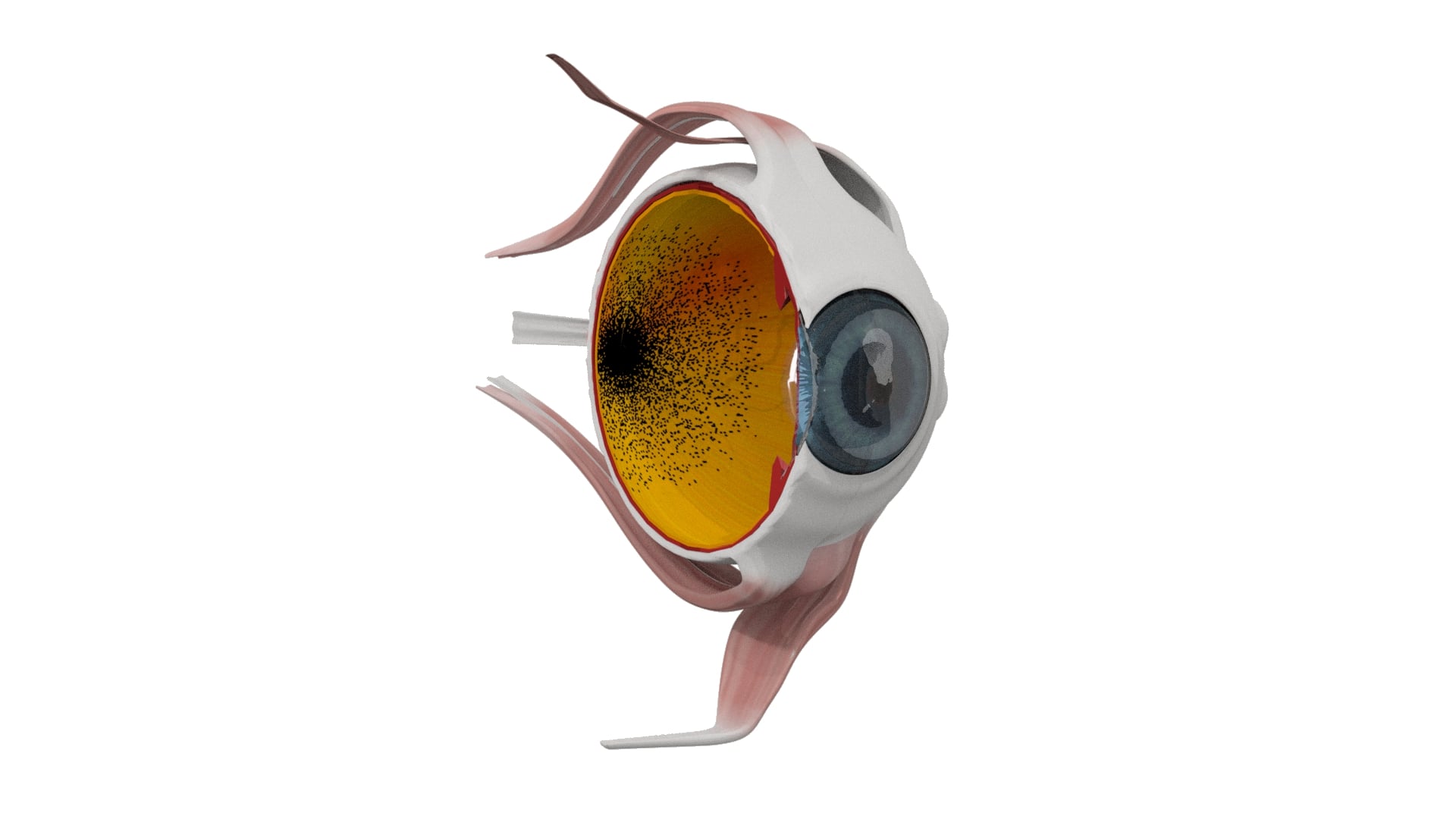

We present a novel, biomimetic model of the eye for realistic virtual human animation. We also introduce a deep learning approach to oculomotor control that is compatible with our biomechanical eye model. Our eye model consists of the following functional components: (i) submodels of the 6 extraocular muscles that actuate realistic eye movements, (ii) an iris submodel, actuated by pupillary muscles, that accommodates to incoming light intensity, (iii) a corneal submodel and a deformable, ciliary-muscle-actuated lens submodel, which refract incoming light rays for focal accommodation, and (iv) a retina with a multitude of photoreceptors arranged in a biomimetic, foveated distribution. The light intensity captured by the photoreceptors is computed using ray tracing from the photoreceptor positions through the finite aperture pupil into the 3D virtual environment, and the visual information from the retina is output via an optic nerve vector. Our oculomotor control system includes a foveation controller implemented as a locally-connected, irregular Deep Neural Network (DNN), or “LiNet”, that conforms to the nonuniform retinal photoreceptor distribution, and a neuromuscular motor controller implemented as a fully-connected DNN, plus auxiliary Shallow Neural Networks (SNNs) that control the accommodation of the pupil and lens. The DNNs are trained offline through deep learning from data synthesized by the eye model itself. Once trained, the oculomotor control system operates robustly and efficiently online. It innervates the intraocular muscles to perform illumination and focal accommodation and the extraocular muscles to produce natural eye movements in order to foveate and pursue moving visual targets. We additionally demonstrate the operation of our eye model (binocularly) within our recently introduced sensorimotor control framework involving an anatomically-accurate biomechanical human musculoskeletal model.

References:

1. A.T. Bahill, M.R. Clark, and L. Stark. 1975. The main sequence, a tool for studying human eye movements. Mathematical Biosciences 24, 3–4 (1975), 191–204.Google ScholarCross Ref

2. W. Becker. 1989. The neurobiology of saccadic eye movements: Metrics. Reviews of Oculomotor Research 3 (1989), 13.Google Scholar

3. I. Bekerman, P. Gottlieb, and M. Vaiman. 2014. Variations in eyeball diameters of the healthy adults. Journal of Ophthalmology 2014, Article 503645 (2014), 5 pages.Google Scholar

4. S.R. Bharadwaj and T.R. Candy. 2008. Cues for the control of ocular accommodation and vergence during postnatal human development. J. Vision 8, 16 (2008), 14–14.Google ScholarCross Ref

5. M. Buchberger. 2004. Biomechanical Modelling of the Human Eye. Ph.D. Dissertation. Johannes Kepler University, Linz, Austria.Google Scholar

6. G. Dagnelie. 2011. Visual prosthetics: Physiology, bioengineering, rehabilitation. Springer.Google Scholar

7. M.F. Deering. 2005. A photon accurate model of the human eye. ACM Transactions on Graphics (TOG) 24, 3 (2005), 649–658.Google ScholarDigital Library

8. W. Fink and D. Micol. 2006. simEye: Computer-based simulation of visual perception under various eye defects using Zernike polynomials. Journal of Biomedical Optics 11, 5 (2006), 054011.Google ScholarCross Ref

9. L.J. Grady. 2004. Space-Variant Computer Vision: A Graph-Theoretic Approach. Ph.D. Dissertation. Boston University.Google ScholarDigital Library

10. J.E. Greivenkamp, J. Schwiegerling, J.M. Miller, and M.D. Mellinger. 1995. Visual acuity modeling using optical raytracing of schematic eyes. American Journal of Ophthalmology 120, 2 (1995), 227–240.Google ScholarCross Ref

11. T. Haslwanter. 1995. Mathematics of three-dimensional eye rotations. Vision Research 35, 12 (1995), 1727–1739.Google ScholarCross Ref

12. K. He, X. Zhang, S. Ren, and J. Sun. 2015. Delving deep into rectifiers: Surpassing human-level performance on imagenet classification. In Proc. IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision. Santiago, Chile, 1026–1034.Google Scholar

13. E. Hecht. 1987. Optics. Addison Wesley.Google Scholar

14. O. Komogortsev, C. Holland, S. Jayarathna, and A. Karpov. 2013. 2D linear oculomotor plant mathematical model: Verification and biometric applications. ACM Transactions on Applied Perception (TAP) 10, 4 (2013), 27.Google Scholar

15. S.P. Lee, J.B. Badler, and N.I. Badler. 2002. Eyes alive. In Proceedings ACM SIGGRAPH. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 637–644.Google Scholar

16. S.-H. Lee, E. Sifakis, and D. Terzopoulos. 2009. Comprehensive biomechanical modeling and simulation of the upper body. ACM Transactions on Graphics 28, 4, Article 99 (2009), 17 pages.Google ScholarDigital Library

17. S.-H. Lee and D. Terzopoulos. 2006. Heads up! Biomechanical modeling and neuromuscular control of the neck. ACM Transactions on Graphics 25, 3 (2006), 1188–1198. Proc. ACM SIGGRAPH 2006, Boston, MA, August 2006.Google Scholar

18. R.J. Leigh and D.S. Zee. 2015. The Neurology of Eye Movements. Oxford Univ Press.Google Scholar

19. M. Lesmana, A. Landgren, P.-E. Forssén, and D.K. Pai. 2014. Active gaze stabilization. In Proc. Indian Conf. on Computer Vision, Graphics and Image Processing. 81.Google Scholar

20. M. Lesmana and D.K. Pai. 2011. A biologically inspired controller for fast eye movements. In 2011 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation. 3670–3675.Google Scholar

21. C.E. Looser and T. Wheatley. 2010. The tipping point of animacy: How, when, and where we perceive life in a face. Psychological Science 21, 12 (2010), 1854–1862.Google ScholarCross Ref

22. M. Nakada, H. Chen, and D. Terzopoulos. 2018a. Deep learning of biomimetic visual perception for virtual humans. In ACM Symposium on Applied Perception (SAP 18). Vancouver, Canada, 20:1–8.Google Scholar

23. M. Nakada, T. Zhou, H. Chen, T. Weiss, and D. Terzopoulos. 2018b. Deep learning of biomimetic sensorimotor control for biomechanical human animation. ACM Transactions on Graphics 37, 4, Article 56 (August 2018), 15 pages. Proc. ACM SIGGRAPH 2018, Vancouver, Canada, August 2018.Google Scholar

24. P. Riordan-Eva and E.T. Cunningham. 2011. Vaughan & Asbury’s General Ophthalmology. McGraw Hill Professional.Google Scholar

25. D.A. Robinson. 1964. The mechanics of human saccadic eye movement. Journal of Physiology 174 (1964), 245–264.Google ScholarCross Ref

26. M. Rosenfield. 1997. Tonic vergence and vergence adaptation. Optometry and Vision Science 74, 5 (1997), 303–328.Google ScholarCross Ref

27. K. Ruhland, S. Andrist, J. Badler, C. Peters, N. Badler, M. Gleicher, B. Mutlu, and R. Mcdonnell. 2014. Look me in the eyes: A survey of eye and gaze animation for virtual agents and artificial systems. In Eurographics State-of-the-Art Reports. 69–91.Google Scholar

28. C.K.L. Schraa-Tam, A. Van Der Lugt, M.A. Frens, M. Smits, P.C.A. Van Broekhoven, and J.N. Van Der Geest. 2008. An fMRI study on smooth pursuit and fixation suppression of the optokinetic reflex using similar visual stimulation. Experimental Brain Research 185, 4 (2008), 535–544.Google ScholarCross Ref

29. E.L. Schwartz. 1977. Spatial mapping in the primate sensory projection: Analytic structure and relevance to perception. Biological Cybernetics 25, 4 (1977), 181–194.Google ScholarDigital Library

30. W.S. Stiles, B.H. Crawford, and J.H. Parsons. 1933. The luminous efficiency of rays entering the eye pupil at different points. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Containing Papers of a Biological Character 112 (1933), 428–450.Google Scholar

31. J.G. Thomas. 1969. The dynamics of small saccadic eye movements. Journal of Physiology 200, 1 (1969), 109–127.Google ScholarCross Ref

32. D. Tweed, W. Cadera, and T. Vilis. 1990. Computing 3D eye position quaternions and eye velocity from search coil signals. Vision Research 30, 1 (1990), 97–110.Google ScholarCross Ref

33. C.-A. Wang and D.P. Munoz. 2014. Modulation of stimulus contrast on the human pupil orienting response. European Journal of Neuroscience 40, 5 (2014), 2822–2832.Google ScholarCross Ref

34. Q. Wei, S. Patkar, and D.K. Pai. 2014. Fast ray-tracing of human eye optics on Graphics Processing Units. Comput. Methods and Programs in Biomed. 114, 3 (2014), 302–314.Google ScholarDigital Library

35. Q. Wei, S. Sueda, and D.K. Pai. 2010. Biomechanical simulation of human eye movement. In Biomechanical Simulation. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Vol. 5985. Springer, Berlin, 108–118.Google Scholar

36. S.H. Yeo, M. Lesmana, D.R. Neog, and D.K. Pai. 2012. Eyecatch: Simulating visuomotor coordination for object interception. ACM Transactions on Graphics (TOG) 31, 4, Article 42 (2012), 10 pages.Google ScholarDigital Library