“Erratics on the road to Wigan Pier: The Creation of TouchAR” by Lewis, Mojsiewicz and Pettican

Conference:

Type(s):

Title:

- Erratics on the road to Wigan Pier: The Creation of TouchAR

Presenter(s)/Author(s):

Entry Number:

- 08

Abstract:

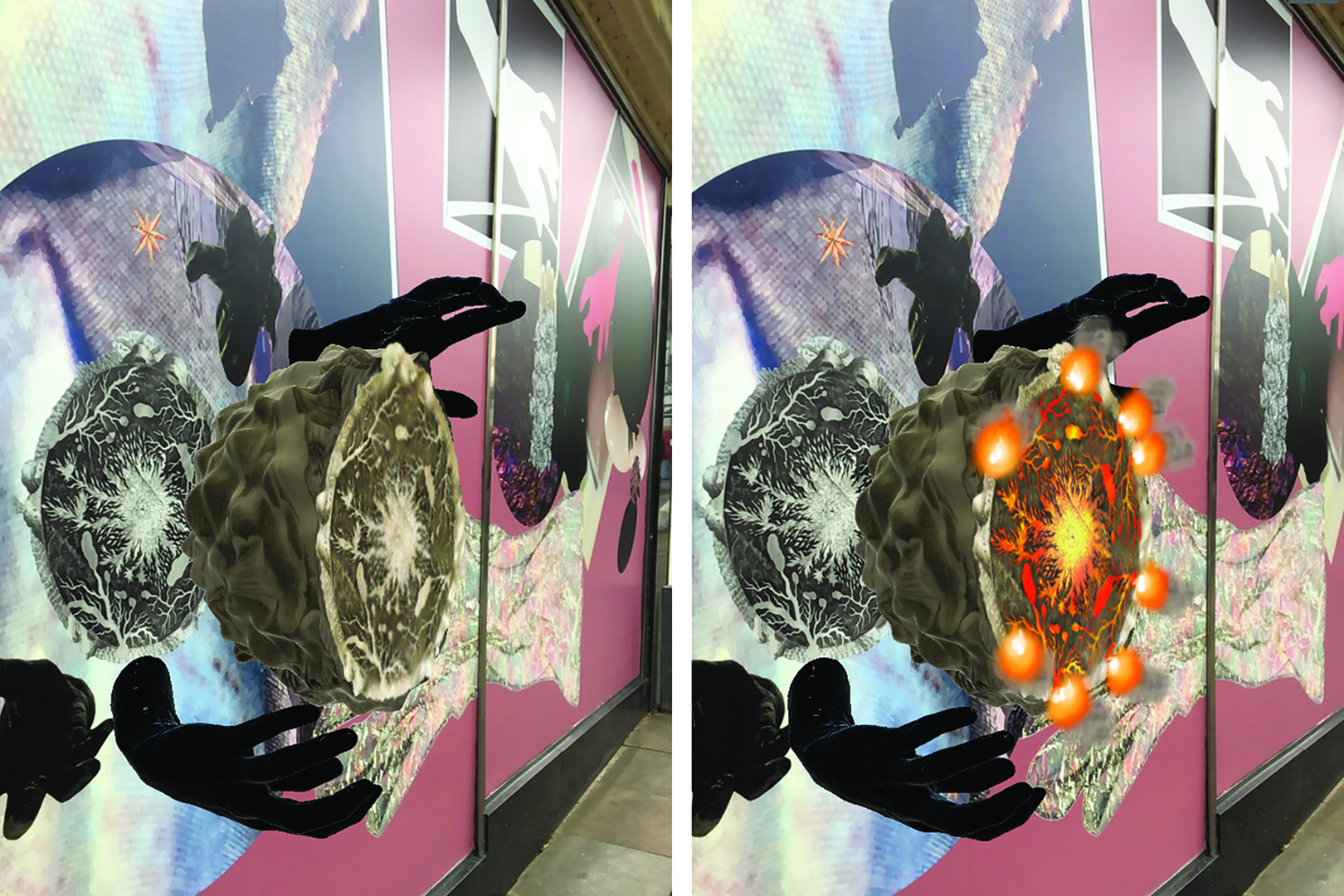

This paper focuses on the augmented reality project TouchAR to reveal creative collaborative approaches the authors took to site, technology, ecology, and gesture in their production of interactive public realm artworks in direct response to the Covid19 pandemic. Informed by the uncanny (re-animation, the double) ontology (affect, sensing embodied encounter) and ecology (speculative fabulation, deep time), the project explores 3D scanning and AR technology as tools for transformation and engagement with ecological deep time; addressing complications involved in offering an embodied experience with AR and as a means of enchantment. The authors will discuss how they use technology to suture analogue and computational art making, explore ideas of touch and engagement with ecology in a technological society and address the deep past, present challenges and possible futures.

References:

Jane Bennett. 2012. Powers of the Hoard: Further Notes on Material Agency. In Animal, Vegetable, Minerals: Ethics and Objects. 2012. Jeffrey Jerome Cohen (Ed.). Oliphaunt Books, Washington, DC. pp. 237–269. DOI: 10.21983/P3.0006.1.00Google Scholar

Barry Cockcroft. 1971. The Road From Wigan Pier. Yorkshire TelevisionGoogle Scholar

David Farrier. 2016. Deep time’s uncanny future is full of ghostly human traces. Aeon. Retrieved 21/01/2022 from https://aeon.co/ideas/deep-time-s-uncanny-future-is-full-of-ghostly-human-tracesGoogle Scholar

Franklin Ginn, Michelle Bastian, David Farrier, & Jeremy Kidwell. 2018. Unexpected encounters with Deep Time. Environmental Humanities, vol.10, no.1, pp. 213-225Google ScholarCross Ref

Donna Haraway. 2016. Staying with the trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press, Durham, NC.Google Scholar

Jane Hutton. 2013. Erratic Imaginaries: Thinking Landscape as Evidence. In Architecture in the Anthropocene: Encounters Among Design, Deep Time, Science and Philosophy. Etienne Turpin (Ed.) Open Humanities Press; University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. pp. 111-124Google Scholar

Athanasius Kircher. 1665. Mundus Subterraneous. Jansson, AmsterdamGoogle Scholar

Darian Leader. 2016. Hands: What We Do with Them – and Why. Penguin Random House, London. ebook ISBN: 9780241973998Google Scholar

Chara Lewis, Kristin Mojsiewicz, & Anneke Pettican. 2020. Gestured by Brass Art: Gestures, Ambiguity and Material Transformation at Chetham’s Library. In Nick Cass, Gill Park, & Anna Powell (Eds.) Contemporary Art in Heritage Spaces. Routledge, London. pp.49-64Google Scholar

Erin Manning. 2007. Politics of Touch: Sense, Movement, Sovereignty. University of Minnesota Press, MinneapolisGoogle Scholar

George Orwell. 2010. The Orwell Diaries. Penguin Books Limited, London. pp. 23-72Google Scholar

Alexander Provan. 2013. Touch Screens. Artforum International. Retrieved 21/01/2022 from https://www.artforum.com/print/201303/touch-screens-39392.Google Scholar